Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), the Scottish born, British Pop art artist worked making collages, graphic works, sculptures, and even mosaic murals. As one of the founders of the British Pop art movement, he is most well known for his early collage I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947).

The Early Years and Education of Eduardo Paolozzi

Born in Scotland, to Italian parents, Eduardo Paolozzi was fascinated by movie stars and machinery. He studied art at Edinburgh College of Art, then at Slade School of Art, in Oxford. Here, the young artist spent many hours drawing the anthropological collections at the Pitt-Rivers museum. Later when the school campus was moved to London, Eduardo Paolozzi spent time studying the works of Picasso and the Cubist form.

Eduardo Paolozzi and his First Solo Show

In his first solo show at Mayor Gallery, in London, in 1947, Eduardo Paolozzi presented Cubist inspired collage and primitive sculpture. The show was a sell out.

A Move to Paris for Eduardo Paolozzi

Later in 1947, Eduardo Paolozzi moved to Paris where his ideas and friendships expanded. Here he met a number of artists who were part of the Surrealist movement including Alberto Giacometti, George Braque, Constantin Brancusi, Jean Arp, and Fernand Leger.

The sculptures Eduardo Paolozzi created during this time illustrated his love of modern machinery, while having an influence of Surrealism. This was also the start of his collage work, using scenes from magazines that represented American culture.

Eduardo Paolozzi stayed in Paris for two years, before returning home.

Eduardo Paolozzi Returns Home

In 1949, Eduardo Paolozzi accepted a teaching position at London’s Central School of Art and Design. With stable employment, the artist was able to set up an art studio. This he shared first with painter Lucian Freud and then with sculptor William Turnbull. During this period, he developed a friendship with Francis Bacon.

Eduardo Paolozzi married textile designer Freda Elliot and moved to the village of Sussex, where he returned every weekend, after his work week in the city ended. Around this time, he also set up Hammer Prints Ltd, with photographer friend Nigel Henderson. The company advertised themselves as specialists in wallpaper and silk-screened textiles.

The Independent Group and Eduardo Paolozzi

Back in London, Eduardo Paolozzi met other artists that would be influential in the development of his career and as an artistic development. The most notable was English born artist Richard Hamilton, who was part of the Independent Group, formed in the early 1950s. This collective of artists, architects, and the art obsessed included not only Hamilton, but art critic Lawrence Alloway, and husband and wife architects Alison and Peter Smith.

The mandate of the Independent Group was to meet and hold lively discussions about art and where it intersected between advertising, books, films, music, popular culture, and new innovative technologies. It was at one of these meetings that Eduardo Paolozzi presented the group with some of his early collages, in 1952. His work, I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947) made a strong impact.

This was the start of the British Pop art movement for which Eduardo Paolozzi was a founder. In fact, the name Pop art is attributed to the Independent Group. The word Pop appears in the artwork I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947).

Eduardo Paolozzi This is Tomorrow

In 1956, artist Eduardo Paolozzi took part in the This is Tomorrow exhibition, at White Chapel Art Gallery, in London’s East End. The event was the pre-cursor to the Pop art movement and extraordinarily successful. In total 38 painters, sculptors, and architects worked in 12 teams to produce artworks. Audiences were welcomed into the interactive exhibition.

A Brief History of Pop Art

Pop Art started in England with the British Pop art movement, but it took root through American consumerism. While Great Britain was still recovering from the devastating aftermath of the war, Americans were shopping for consumer goods and new household appliances. This was popularized in advertising, magazines, books, and films.

The Pop art movement was a radical shift in art, blending both popular art and popular culture. What started in England rapidly moved to New York and later Los Angeles. These cities were filled with artists creating Pop Art.

Richard Hamilton described it as “Pop art is: Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business.”

For more information, see our article on Pop Art History.

The Bunk Series

Eduardo Paolozzi created several collages between 1947 and 1952, which he called the Bunk series. The title came from Henry Ford’s statement, “History is more or less bunk… We want to live in the present.” The images in the collages represent what was current, using images focusing on aviation, science fiction, advertising, foods, and film.

Some of the best recognized collages Eduardo Paolozzi created during this period include I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947), Dr Pepper (1948), Lessons of Last Time (1948), Sack-O-Sauce (1948), Was This Metal Monster Master or Slave? (1948), It’s a Psychological Fact Pleasure Helps your Disposition (1948), Meet the People (1948), Wind Tunnel Test (1950), Real Gold (1950), Yours Till the Boys Come Home (1951), and The Ultimate Planet (1952). These Eduardo Paolozzi works are on display at the Tate Gallery, in London, United Kingdom.

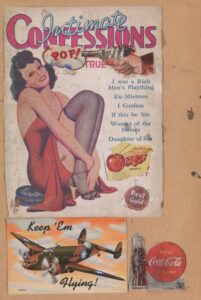

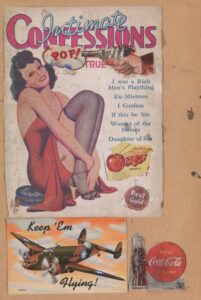

I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947)

I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947) by Eduardo Paolozzi is one of the artist’s early Pop art collages. In the center is and pinup girl image from an American magazine. Beside her is a slice of cherry pie and an over enlarged cherry. At the bottom are cut outs of a World War II bomber and a bottle of Coco-Cola with the company logo. The word “POP!” emerges from a pistol aimed at the head of the smiling girl. It is held by a man, yet only his hand and sleeve are visible.

I was a Rich Man’s Plaything from 1947, by Eduardo Paolozzi is part of the collection at the Tate Gallery, London, United Kingdom.

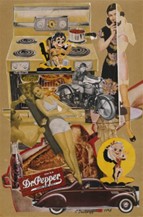

Dr. Pepper (1948)

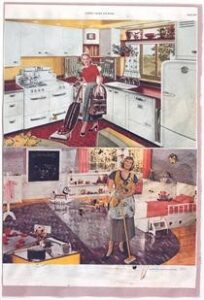

In 1947, food rations in Britain were intense. In Paolozzi’s work he reflects his hunger with a collage named after the popular Dr. Pepper soft drink and a montage of the American good life. The electric oven, holds a pot with a homecooked meal ready for consumption.

Pin-up girls as found in popular American magazines make the cut, shown in under garments. A motorcycle and car portray the artist’s fantasy with modern machinery.

Dr Pepper (1948) by Eduardo Paolozzi is part of his Bunk series. It’s on view at the Tate Gallery, in London, United Kingdom.

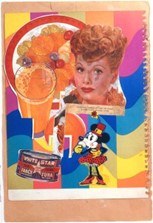

Meet the People (1948)

Meet the People (1948) is another collage where Eduardo Paolozzi focuses on the idealized American lifestyle and popular culture.

The upper photo shows a full American breakfast, with pancakes, fruit, and the ever-present morning glass of orange juice. Next to it is a photo of the actress Lucille Ball, in her youth. Below, is the cartoon version on glamor, Disney’s colorful Minnie Mouse. In the bottom left is the convenience supermarket product White Star Fancy Tuna.

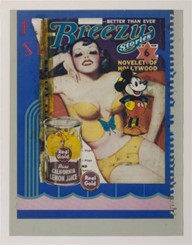

Real Gold (1950)

Real Gold (1950) the Eduardo Paolozzi collage, using print paper on card, is another work that is part of the Bunk series. Here, the color in the title is reflected in the starlet’s bikini and the can of Real Gold California lemon juice, a commodity on the left. Disney’s Mickey Mouse is also part of this collage work. The mouse, a symbol of American childhood, as well as other Disney characters are reoccurring images in the work of Eduardo Paolozzi.

Cyclops (1947)

Eduardo Paolozzi made two sculptures, in 1947, that were both called Cyclops. One is of a head, and the other is a full figure. Cyclops (1947) is named after the one-eyed giant in classical Greek mythology that lived in a tribe with other giants, on an island in Greece.

Eduardo Paolozzi and his fascination with machinery is apparent in these works. Notice the eye in the center of the full figure Cyclops, fashioned as a wheel. Uniquely, the entire work is imprinted with machine parts such as cogs, locks, and scrap metal, as well as pieces from nature, including wood and bark.

Other objects were used in the Cyclops over-sized head sculpture. Eduardo Paolozzi listed car wrecking grounds in his hunt for pieces saying the following went into the work, “Dismembered lock. Toy frog. Rubber dragon. Toy camera. Assorted wheels and electrical parts. Clock parts. Broken comb. Bent fork. Various unidentified objects. Parts of a radio. Old RAF bomb sight. Shaped pieces of wood. Natural objects such as pieces of bark. Gramophone parts. Model automobiles. Reject die castings from factory tip sites.”

Unlike classical sculptures, which idealized the human body, Cyclops (1947) in full figure, is only the representation of a human form. This work by Eduardo Paolozzi, although recognized as a human form is only an approximation. It does not have hands, or feet or joints.

Eduardo Paolozzi crafted the Cyclops sculptures by using the lost-wax method of making bronze sculptures. First the artist made a clay model, in which he made the impressions with the objects. To make the model, he used a clay or plaster bed. Once hot wax was poured over, he formed the sculptures. The model was then set in clay, with a hole cut in the bottom.

Once heated, the wax dripped out leaving an impression in the clay interior, and a gap between it and the clay model. Then, the work was tipped upside down and the bronze poured in to set. When dry, it was tilted upward, and the clay cracked off.

Eduardo Paolozzi left the holes in the bronze sculptures, which although unintentional, happened during casting. These holes make the viewer aware it is hollowed. Additionally, it gives it a look of decay. Today, these bronze works by Eduardo Paolozzi resides in the collection of the Tate Gallery, in London, in the United Kingdom.

The Silken World of Michelangelo from Moonstrips Empire News (1967)

The Silken World of Michelangelo is one of a number of pieces produced for Moonstrips Empire News. Here, Eduardo Paolozzi uses screenprint, a medium that fellow Pop art artist Andy Warhol would later popularize. The Disney cartoon character Mickey Mouse appears on the right, while David by Michelangelo, the Italian Renaissance artist who inspired this work, appears on the right. These images have the look of being digitalized. Both images work to combine consumer culture with fine art.

Mosaic for Tottenham Court Road Tube Station (1979)

The mosaics at Totten Court Road, in London, is a colorful and vibrant work of public art by Pop art artist Eduardo Paolozzi. Located at the Tottenham Court Road Tube Station, the mosaics made from vitreous, smalti and piastrelle, stretching along 1000 sq meters, is filled with scenes from popular culture and everyday life.

In 2015, part of the mosaic had to be removed to accommodate the expansion of the area. Almost 95 percent was replaced piece by piece on the new walls. The small portion that had to be eliminated was donated to the Edinburgh College of Art.

Eduardo Paolozzi Art on View

The Tate Gallery, in London has an ample collection of works by British Pop art artist Eduardo Paolozzi . The artist donated a considerable proportion of his work to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, in 1994.

Eduardo Paolozzi Legacy

Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi was knighted in 1989. His unique art led to the British Pop art movement, where he earned his place in Pop art history.