Futurism is an avant-garde art and social movement that originated in Italy. Several manifestos were created in the wake of futurist philosophy and the most important of them was the Manifesto of Futurism, published by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909. The attitude towards the past that the Futurists had was based on an uncompromising rejection of tradition. On the other side, Futurists were glorifying the cult of youth, industrialization, speed, technology, and modernization. Futurists were often emphasizing the violent component of the struggle for cultural and wider social change. Futurism developed in literature as well as in painting, sculpture, architecture, industrial design, music, film, dance, and fashion.

The characteristics of futurism include: the rejection of traditional value frameworks in the field of culture, ie striving for art freed from the weight of its past, highlighting youth as a key capital of social development, technology, modernization of urban spaces, the dynamism of industrial plants, exploring speed through the representation of objects such as cars or airplanes.

Notable Futurists were : Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carrà, Gino Severini, Gerardo Dottori, Fortunato Depero, Luigi Russolo, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Antonio Sant’Elia.

Futurism influenced Art Deco, Cubo-futurism, Constructivism, Rayonism, Vorticism, and Precisionism.

What is Cubism?

Cubism is an avant-garde art movement that originated in France. The originators of this revolutionary artistic practice were Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. The very beginning of Cubist practice dates back to 1907-1908. The work of Paul Cezanne played a key role in the creation of the new Cubist philosophy of painting. His principles of colored fields, experimentation with perspective and the idea of reducing all forms in nature to the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone became the basis for the development of the cubist method. Cubism formulated a new painting based on mobile perspective and geometrization of scenes. This procedure was created with the aim of achieving the authentic two-dimensional nature of the image.

The characteristics of cubism include the frequent use of mixed media/collage, insistence on flatness or two-dimensionality as the primary characteristic of the image, the rejection of the traditional understanding of perspective, as well as the creation of a new principle of mobile perspective. Cubism also rejects the conventional approach in the domain of the use of shadow and light. Geometrization and fragmentation of scenes, which are achieved by treating multiple planes simultaneously, are the most recognizable characteristics of Cubist expression, which separate it from mimetic principles in painting.

Notable Cubists were: Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, André Lhote, Francis Picabia, Alexander Archipenko, František Kupka.

Cubism influenced Orphism, Vorticism, Purism, Precisionism, Cubo-futurism, Constructivism, De Stijl, Art Deco, Rayonism, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Op Art.

Futurism and Cubism Similarities

The most prominent similarities between Cubism and Futurism are the influences of Paul Cezanne’s painting method, divisionism, geometrization, fragmentation of objects, mobile perspective, and experimentation with the collage technique.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Paul Cezanne’s painting

The painting of Paul Cezanne was crucial for the development of the painting of the early avant-garde movements. Cezanne presented a new structure of painted composition, which was primarily reflected in the principles of inverse perspective. This revolutionary component of his painting will prove to be very significant for the painting of Cubism and Futurism. In contrast to linear perspective, which was the basis of Western painting for centuries, inverse perspective was developed by Byzantine painters throughout the Middle Ages. Cezanne’s use of inverse perspective made it possible to represent those segments of painted scenes that would not be visible in a traditional linear concept. In addition to the inverse perspective, the geometrization of scenes had a strong influence on the further development of modern painting. Paul Cezanne claimed that all phenomena in nature can be represented through three geometric bodies: a sphere, a cone, and a cube. Cubism will develop this principle and create a new revolutionary painting language that will later be appropriated by Futurism.

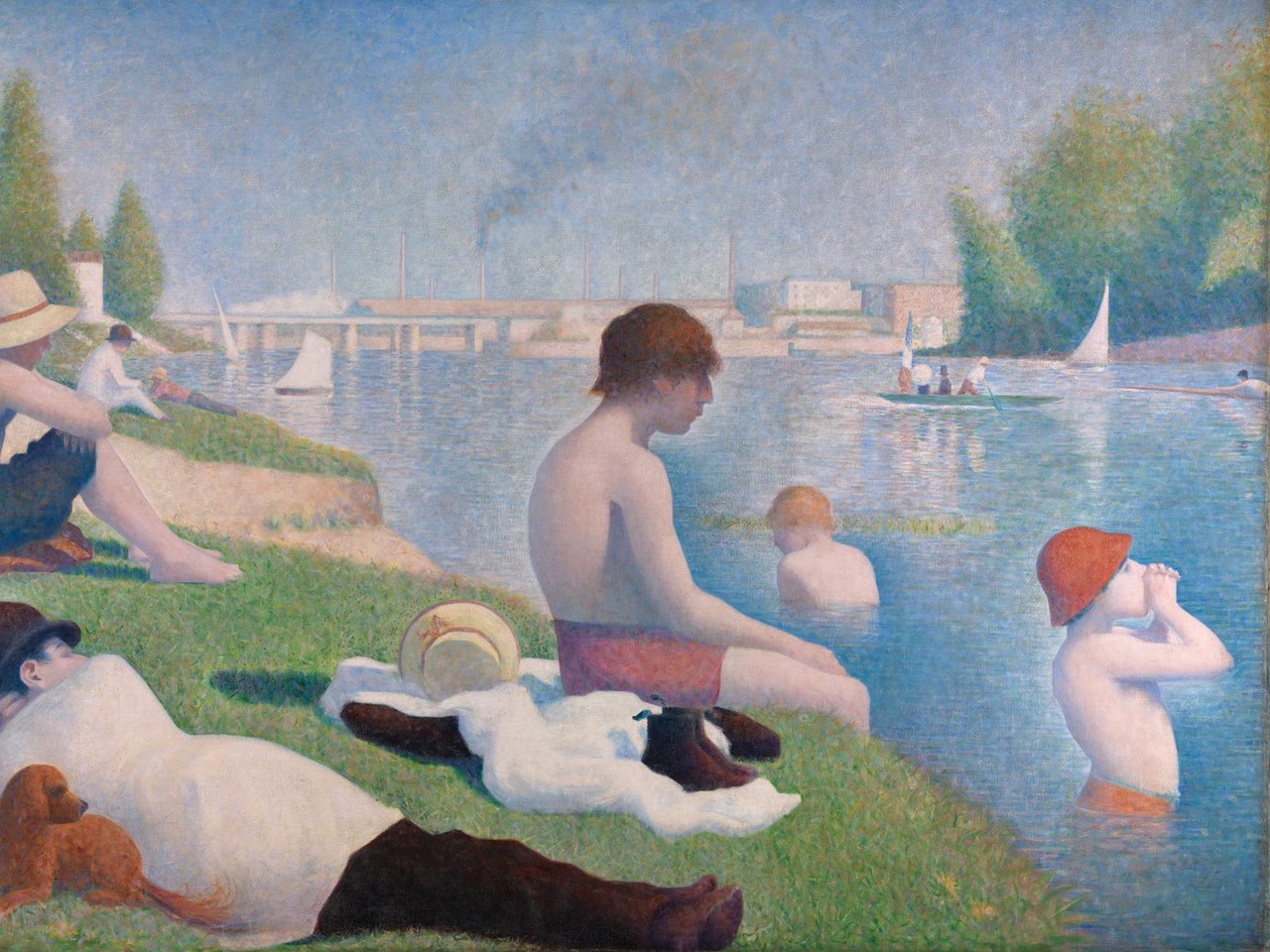

Futurism vs. Cubism: Divisionism

The art of Post-Impressionism greatly influenced Cubism and Futurism. Besides Paul Cezanne, the artist whose influence is most visible is Georges Seurat. Georges Seurat’s innovative approach to color known as Divisionism brought a scientistic attitude to the palette that was based on the optical research of the time. Divisionism meant applying paint to the canvas in its pure form, that is, without previously mixing the pigment on the palette. Georges Seurat believed that by appropriately positioning contrasting colors, an improved effect of image brightness is achieved. The divisionist technique was strongly represented both among the Cubists and among the Futurists.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Geometrization

Geometrization is one of the key elements of Cubist and Futurist painting. By departing from the traditional principles of mimetic painting, cubism generated a new language of which geometrization was a significant part. Geometrization achieved the effect of flatness – authentic two-dimensionality that belongs to the medium of painting. In defining this method, Cubists were guided by the ideas of Paul Cezanne about the possibility of reducing all scenes in nature to geometric bodies. The Futurists completely took over this painting formula, emphasizing geometrization as a component that unites the language of technique and the language of visual art. Geometrization was developed in futuristic painting not through the prism of the genesis of the artistic language to authentic two-dimensionality, as is the case with Cubism, but through the visual prism of modernization, industrialization, and the technological revolution that it was meant to point to.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Fragmentation

Futurism adopted the Cubist principles of scene fragmentation. As a continuation of Cezanne’s ideas about the new visual capacities brought by the inverse perspective, the Cubists divided the scene into several angles from which it can be viewed. Fragmentation has become a major tool for deconstructing traditional perspective frames. This procedure was developed by the Futurists, especially in the domain of representing the dynamism of urban spaces as well as the speed of cars or people in motion.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Mobile perspective

Post-impressionism, especially Cezanne’s research on inverse perspective, opened the way for Cubists and Futurists to a more revolutionary experiment. The concept that Cezanne reactualized referred to the principle that not all objects in a painting need to be represented from the same point of view. This method was developed by the Cubists by simultaneously including numerous viewing angles for each represented object. Cubists achieved the impression of the overall visuality of the scene through intensive geometrization and fragmentation. On the same track, the painting of Futurism developed a mobile perspective that largely formed the painting language of this movement, which was based on the themes of speed, the dynamics of modern urbanization, revolutionary technological advances, etc.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Collage technique

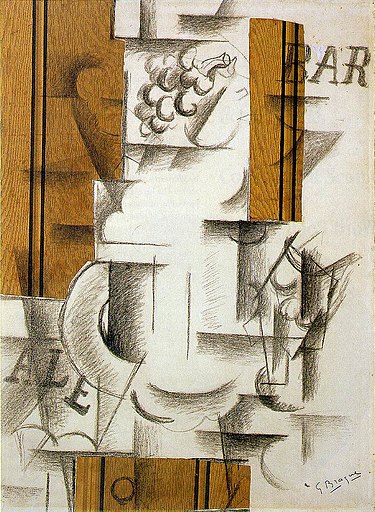

Georges Braque first applied the collage technique to the 1912 Fruit Dish and Glass charcoal drawing. This invention took place during a summer in Sorgues in the south of France, where Pablo Picasso and Braque worked together. The still life is what the Cubists most often represented with this technique. The phenomenon of introducing material that was not created for the needs of the painting by artistic means, but on the contrary is a widely available industrial product – opened the question of the authorship limits. Futurists adopted this technique and developed it in different directions. Carlo Carra often used collage very freely and incorporated it into complex geometric units, as in the example of the painting Interventionist Demonstration, 1914. Umberto Boccioni, on the other hand, in the painting Under the Pergola in Naples from 1914, uses collage subtly and discreetly relying more on early Cubist works.

Futurism and Cubism Differences

The differences between Cubism and Futurism relate to the approach to the phenomenon of speed, the role of publishing multiple Manifestos, as well as to differences in the domain of political engagement.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Speed

In addition to industrialization, the technological revolution, and the process of urbanization, the Futurists were preoccupied with the phenomenon of speed. Cubists achieved dynamism in a painted composition with a mobile perspective, which often represented a static scene. That dynamic was further enhanced by the fragmentation of the object, while the composition essentially remained static. The Futurists went a step further and strived for visual solutions that would translate the illusion of movement and speed into the language of painting most effectively. Thus, cars in motion, runners, cyclists, and dancers, became frequent motifs of futuristic art. Using the cubist tools of mobile perspective and fragmentation of the scene, the Futurists primarily sought to express speed as one of the leading values of the modernization process.

Futurism vs. Cubism: The manifestos

Futurists paid great attention to theoretical work and the publication of numerous publications. The format of the manifesto was characteristic of many avant-garde movements, but the Futurists led the way with the number of published manifestos from various fields of artistic creativity. In addition to being distributed as pamphlets, manifestos were often published in newspapers. It was a very successful way of communicating with the audience. Some of the Futurist manifestos are The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism, (1909), The Manifesto of the Futurist Painters (1910), Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1910), Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture (1912), The Manifesto of Futurist Musicians (1912), Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (1914), The Futurist Cinema (1916), as well as probably the most famous futurist text A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1917), by David Burliuk, Alexander Kruchenykh, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Victor Khlebnikov. The Cubists did not pay too much attention to the writing of manifestos, so the few earliest texts that laid the foundations for the study of Cubism were written by art historians and theorists who collaborated with the Cubists. The most famous examples of those works are Du Cubisme (1912), by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, Anecdotal History of Cubism (1912) by André Salmon, and The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations (1913), by Guillaume Apollinaire.

Futurism vs. Cubism: Political engagement

Cubism, although an influential artistic movement in the international framework, did not articulate its action through political engagement. The themes that preoccupied the Cubists were revolutionary in an artistic context. The spectrum of political orientations that the Cubists had was very heterogeneous, although the Cubist aesthetic is associated dominantly with left-wing political options. On the other hand, the Futurists at one point became a clearly politically profiled organization. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party in 1918. The Futurists were part of the nationalist political wave that rested on the ideas of restoring the old Italian power through unification with compatriots who lived on the territory of Austria-Hungary. The glorification of war and violence as a way of salvation through a revolution were ideas openly supported by the Futurists. In 1919, the Futurist Political Party became part of Mussolini’s organization Italian Fasces of Combat, later reorganized as the National Fascist Party. One of the authors of The Manifesto of the Italian Faces of Combat was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

How did Cubism Influence Futurism?

Cubism had a crucial influence on the artistic expression of Futurism. Although these two movements developed almost simultaneously, Cubism, as the oldest avant-garde movement, influenced the path of visual development of Futurism. That influence was reflected in continuity with the post-impressionist ideas of inverse perspective and divisionism. Cubism also introduced a language of strong geometrization with a tendency towards abstraction, which the Futurists built upon. The collage technique often used by the Futurists was invented by the Cubists. One of the most significant characteristics of futurist painting is authentically cubist and refers to a mobile perspective.

What other Art Movements are Similar to Futurism and Cubism?

The influences of both the Cubist and Futurist movements on modern art were very strong throughout the twentieth century. Numerous artistic phenomena were created and developed based on the ideas of these two avant-garde movements, among which stand out: Orphism, Vorticism, Purism, Precisionism, De Stijl, Art Deco, Rayonism, Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Op Art.