Cubism emerged in France around 1907 and lasted until 1914. Cubist artwork typically features a fragmented composition representing the subject from all angles with overlapping, geometric planes. Artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque led Cubism through its phases: Proto-Cubism, Analytical Cubism, and Synthetic Cubism.

Impressionism is a style of painting also developed in France during the mid-to-late 19th century, from around 1874-1886. The Impressionist movement was founded by Paris-based artists Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Fédéric Bazille, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas.

The Impressionist painting style includes small, visible brushstrokes that offer an essential impression of form, unblended color, and an emphasis on accurately depicting natural light. As a result, Impressionist paintings were typically bright with bold colors and a contrasting color palette.

Cubism and Impressionism have many similarities, with the three most significant being the use of broken and constructive brushwork, rejecting the strict rules of academic painting, and being representational.

Three main differences between Cubism and Impressionism are the subject matter, the use of color, and the element of time.

Cubism and Impressionism Similarities

Cubism and Impressionism have many similarities, with the three most significant being the use of broken and constructive brushwork, rejecting the strict rules of academic painting, and being representational.

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Broken and Constructive Brushwork

Broken brushwork refers to the quick, sketch-like brushstrokes that Impressionists used to represent their subject matter. Impressionist artists used short, visible dabs of paint to capture the overall impression of their subject, consciously overlooking the fine details.

Constructive brushwork refers to meticulously arranged brushstrokes that work together to build shape and form with areas of color rather than unbroken, black lines. Cubists also used small brushstrokes built up to form visually complex, overlapping planes.

Characteristically Impressionist brushwork is seen in Claude Monet’s Impression Sunrise, below:

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Rejecting the Academy

Cubist and Impressionist painters rejected classical subject matter and the hierarchy of genres established by the French academy in the 17th century. Cubist and Impressionist paintings are defined by their sketch-like, fragmented appearances due to artists rejecting the academic traditions of perspective, modeling, and foreshortening.

For Cubist artists, this meant overlapping perspectives, avoiding value gradations, and abandoning the illusion of depth. Impressionist painters applied pure colors directly to their canvases without mixing, deemed harsh and unrefined by the academy. Impressionists also used short, visible brushstrokes, unlike academic artists’ wholly smooth and seamless aesthetic. Impressionists also abandoned the tradition of painting in a studio using dramatic studio lighting; they preferred to paint outdoors using natural light.

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Representational Style

Cubism and Impressionism are both considered to be representational styles of visual art. However, compared to pre-modern art movements and due to broken brushwork, both Cubism and Impressionism appear to lean towards abstraction. While both movements play with the conventions of representation, their subjects remain recognizable to the viewer.

Juan Gris’ Portrait of Pablo Picasso seen below depicts fellow Cubist Pablo Picasso in the Analytic Cubism style, with many planes and perspectives, while the subject remains identifiable as a seated person:

Cubism and Impressionism Differences

Three main differences between Cubism and Impressionism are the subject matter, the use of color, and the element of time.

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Subject Matter

Cubist paintings were often portraits. Using people as subject matter lent itself well to Cubism’s concern for representing reality from multiple angles. While portraits were typical in the earlier phase of Cubism, later Cubist artists expanded their subject matter to include still lifes and landscapes.

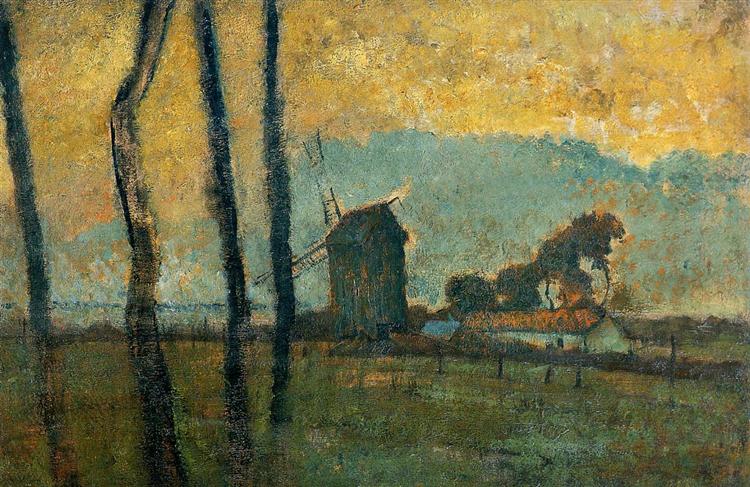

Unlike Cubism, capturing the effects of light on landscapes was a primary concern of Impressionist painters, which is why so many Impressionist paintings feature landscapes as subject matter. Rather than work in a studio, many Impressionists preferred to paint en plein air, or outdoors. Painting outdoors required the artists to work quickly but allowed them to accurately capture the fleeting impressions of light on land, sea, and sky.

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Color

Cubist paintings, particularly those of the Analytic Cubism phase, have a monochromatic color palette using dark, earthy tones. Cubists also used black and shades of gray paint to depict shadows.

On the other hand, Impressionist painters paired complementary colors to depict shadows instead of using black and gray paint. The paints themselves were brighter than those used in previous art movements due to the invention of synthetic pigments, which made paint mixing easier and expanded an artist’s mobility beyond the studio.

Impressionism’s bright hues are evident in Edgar Degas’ Landscape at Valery-sur-Somme, pictured below:

Cubism vs. Impressionism: Time

Cubist and Impressionist artists treat the passing of time differently within their paintings. Cubist artists depict various perspectives simultaneously rather than in the sequential order that a viewer might naturally experience while displaying all of a subject’s possible viewpoints and flattening time into a single instance.

Meanwhile, Impressionism captures a single, fleeting moment in time determined by natural light. Impressionist painters were particularly interested in how natural light illuminated a landscape during a natural event such as a sunrise or sunset.

How did Impressionism Influence Cubism?

Impressionism influenced Cubism through Impressionist techniques such as “broken” brushwork and “constructive” brushwork. Both techniques were carried from Impressionism through post-Impressionism by French painter Paul Cézanne. Cézanne spent a brief time painting with the Impressionists in the late 1800s. Cézanne’s post-Impressionist techniques and methods were adopted and expanded by legendary Cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

What are Other Art Movements Similar to Cubism and Impressionism?

Cubism and Impressionism are similar to Expressionism, which emerged in Northern Europe around the start of the 20th century and lasted from around 1905-1920. Expressionist painting typically presents the world from a subjective perspective, radically distorting subject matter for emotional effect to evoke moods or ideas.

Cubism, Impressionism, and Expressionism emerged in opposition to Realism and Naturalism. Compared to Cubism and Impressionism, Expressionism is also a relatively abstract painting style, though this varied between artists. For example, Vassily Kandinsky’s work is entirely abstract, whereas the work of Edvard Munch is representational.

Much like Cubism, Expressionism was influenced by Fauvism, which explains Expressionism’s tendency toward jarring compositions and bright, sometimes arbitrary, colors. The Cubist and Expressionist movements coexisted with numerous other art movements that emerged in the early 1900s.

Cubism, Impressionism, and Expressionism explored similar themes in response to the effects of modernization and industrialization. Expressionists were also concerned with conflicts in human morality brought about by industrialization and the First World War.