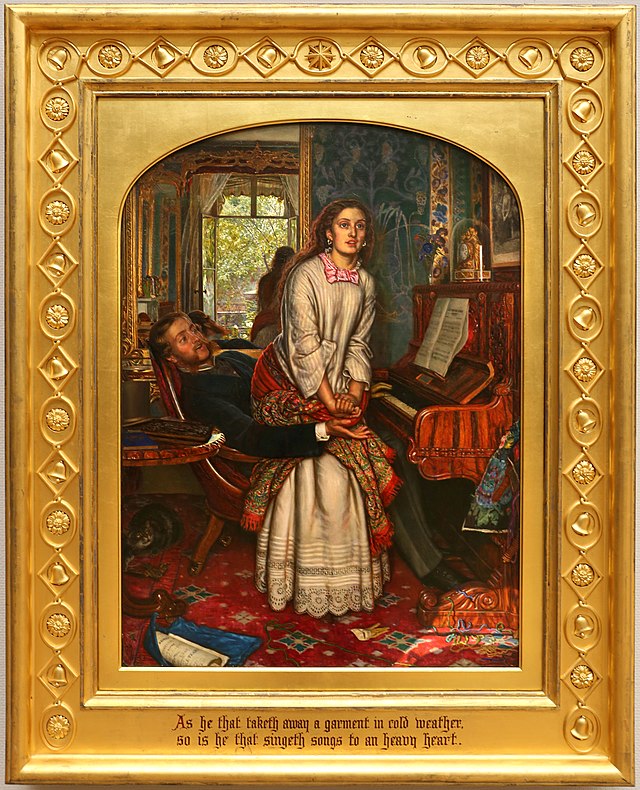

The Awakening Conscience is a didactic genre scene by Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt. Completed in 1853, the oil on canvas measures 76 x 56 cm. It was initially commissioned by Thomas Fairbairn. Fairbairn, the owner of an engineering company in Manchester, paid 350 guineas for the work, but was unsatisfied with the face of the woman. Between 1856 and 1857, Hunt retouched the work, repainting the face to satisfy Fairbrother. Hunt exhibited both this painting and The Light of the World at the Royal Academy in 1854.

Fairbairn’s son, Sir Arthur Henderson Fairbairn inherited the painting in the early 20th century. It was purchased by Sir Colin Anderson in 1947 after being sold at Christie’s in January of 1946. Anderson and his wife donated the canvas to the Tate Gallery in 1976. Currently, it is housed in the Tate Gallery in London, England.

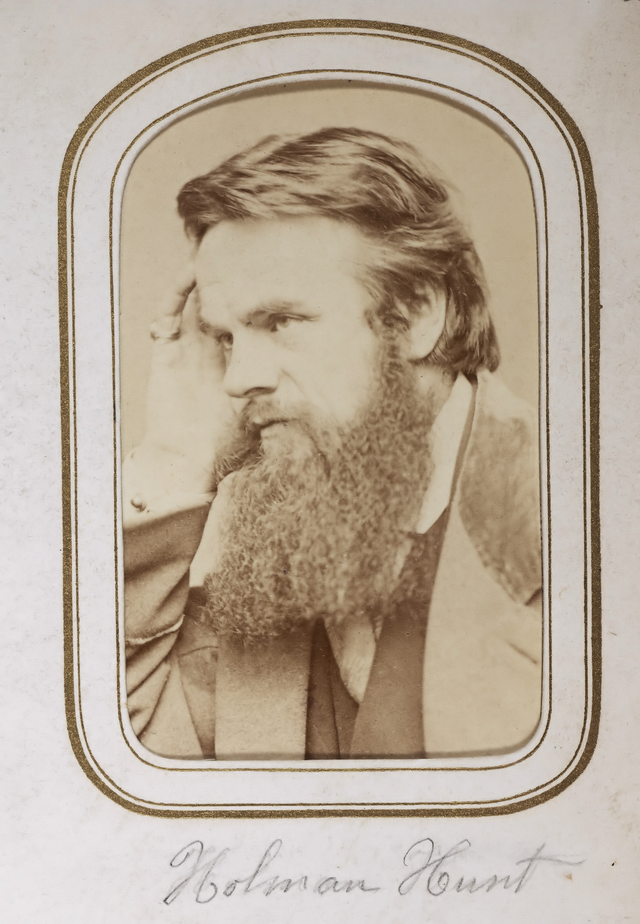

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt was born in London in 1827. His father was a merchant and his mother from a wealthy family. His first wife, Fanny Waugh died in childbirth and Hunt subsequently married her sister Edith. Initially he tried to attend, but was rejected, from the Royal Academy. Hunt did eventually attend the Royal Academy, where he met John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The three students left the academy and founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848.

The Pre-Raphaelite art movement was pioneered by a group of English artists, poets, critics, and playwrights. Pre-Raphaelite paintings emulated early Italian art and was opposed to the classical compositions that Raphael made popular and that had become popular in Victorian art at the Royal Academy.

The founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), Dante Gabriel Rosetti (1828-1882), and John Everett Millais (1829-1896). Other members of the Pre-Raphaelite movement include William Michael Rossetti, Frederic George Stephens, James Collinson and Thomas Woolner. Hunt was known to paint religious subjects in a naturalistic and Pre-Raphaelite manner. Hunt’s religious paintings were a huge influence on nineteenth century British art and Victorian society. Hunt maintained a dedication to religion throughout his life. Hunt’s unwavering belief in Christianity colored his viewpoint.

Hunt lived the longest of the three Pre-Raphaelite founders, living until 1910, where he died in London.

Images of The Awakening Conscience

What is Depicted in the The Awakening Conscience?

William Holman Hunt’s painting The Awakening Conscience in 1853. The oil on canvas features a young woman who is rising from her lover’s lap. The couple are engaged in an affair, proven by the newly decorated interior. We are made to understand they are not married because of the lack of wedding ring on her finger. Additionally, the furniture and the embossed books are brand new, and many symbolic references point to the woman being a kept woman rather than married to the gentleman.

In The Awakening Conscience we are witnessing the moment of spiritual revelation that the young unmarried woman is having. Contemporary cultural references help the Victorian viewer, and us, to understand the setting and story. First, there is a print on the wall by English artist Frank Stone (1800-1859). The print is called “Cross Purposes.” On the floor to the left is Edward Lear’s (1812-1888) musical arrangement of the poem “Tears, Idle Tears” by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) from 1847. Also, the sheet music on the piano is Thomas Moore’s “Oft in the Stilly Night.” The song laments on happy past memories and missed opportunities for the future. In order to replicate the setting with accuracy, Hunt rented a room in St. John’s Wood. This room typically used for meetings like the one pictured, was located at Woodbine Villa, 7 Alpha place.

The Awakening Conscience Analysis

The Awakening Conscience was initially created as a counterpart to The Light of the World (1851-1854). The earlier painting features Jesus outside ready to knock on a door. Conceptually, The Awakening Conscience shows the woman answering Jesus’s knock and letting Jesus in. Hunt’s redemptive message was mostly well received within the Royal Academy. While some critics ignored the religious messages evident in Hunt’s painting, art critic, and Pre-Raphaelite supporter, John Ruskin. (1819-1900) vehemently defended the work in the Times.

Though to us, the interior is characteristic of Victorian England, to the contemporary audience it would have been uniquely different from the Victorian family home. The so-called fatal newness of the furniture would have signified a falseness to people in the 19th century. Hunt played into a standard narrative, which Victorian viewers would have immediately understood, that this was a fallen or “kept” woman. Therefore, the moment we witness is one following a tryst.

Hunt’s heroine has realized her mistakes and stands up from her lover’s lap. A potential cause for the woman’s awakening conscience is that the man, playing the sheet music resting on the piano has triggered a memory for her. She remembers her past innocence and has a spiritual awakening. At this moment of redemption, she stands up, realizing the error of her ways. She gazes out of the window into nature, which the viewer sees through the mirror in the background. The underlying spiritual message is poetic in that the Pre-Raphaelite believed that in nature one found truth. Thus, the woman was finding truth, God, or both by glancing outside. Though the mirror image represents the woman’s lost innocence, it also hints at her redemption.

Hunt took inspiration from Dutch interiors, like Jan van Eyck’s The Double Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife, or the Wedding Portrait (1464), which he likely saw at the National Gallery. Another inspiration was English artist William Hogarth’s Marriage-a-la-mode series, which told the story of extramarital affairs and the breakdown of a domestic home. In both cases, the paintings used objects around the room to symbolize things and tell the story of what was occurring. In other words, these paintings and the Awakening Conscience could be read through understanding the textual and various symbolic emblems within the work.

Hunt used symbolic references to tell the story. For example, the cat toying with the bird in the left foreground, suggests adultery and infidelity. It also hints at the concept that the woman has been caught by the man as the cat caught the bird. Another symbol of the woman’s trapped nature is the clock that is hidden underneath the glass. The discarded glove and top hat are symbols for the tryst that has just occurred. Another sign that the woman is headed down the wrong path is the unraveling yarn hanging on the piano. The unraveled yarn, tangled on the ground is a symbol of the entanglement of the young girl.

Symbolically, Hunt portrays a woman who is rising from a depraved or fallen state. The young woman springs up having heard the call of Christ and gazes outside of the canvas towards a “better” life. We can tell from the mirror in the back of the canvas that she is gazing out of a window at nature. This suggests that nature is the ultimate view of God and represents the ultimate truth. To this point, Hunt inscribed a verse from the Bible on the frame. Proverbs 25:20 reads, “as he that taketh away a garment in cold weather so is he that singeth songs to an heavy heart.” Hunt creates a positive spiritual message by first relaying the sinful nature of the man and the woman as a victim. The young woman is then able to be redeemed by having her inner conscious awakened to God’s presence after hearing a song.

As with many of the other Pre-Raphaelite painters, Hunt uses flowers to correspond to the Victorian language of flowers, where flowers represented emotions or situations. In The Awakening Conscience, Hunt includes marigold flowers on the frame. Marigolds corresponded to sorrow in the well-known Victorian language of the flowers.

Moreover, some of the Pre-Raphaelite members began designing their own frames and incorporating a unique style of frame as part of their whole aesthetic. The flat-ornamental gold frames often incorporated organic plant shapes as well as geometric symbols. In Hunt’s case, he designed the frame to incorporate symbolic references to the theme of the painting. First, the marigolds and also a star to signal spiritual revelation.

Who is the model in the Awakening Conscience?

Hunt hired his girlfriend Annie Miller (1823-1935) to model for the face of the young unmarried woman engaged in the affair. Hunt’s girlfriend Annie Miller, worked in a bar in 1850, when he found her at the age of 15. Therefore, Hunt’s work reflects his own experience with “saving” Miller from being a fallen woman. Hunt and Miller were engaged for a time before he married Fanny Waugh (d. 1866). The male figure was likely modeled by one of Hunt’s friends, possibly Thomas Seddon (1821- 1856) or Augustus Egg (1816-1863).

Where is the Awakening Conscience currently located?

The Awakening Conscience is in the Tate Britain in London, England.

Other Artwork by the Artist

- The Hireling Shepherd, 1851

- The Light of the World, 1854

- Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1868

- The Lady of Shalott, 1905

Citations:

- Calloway, Stephen and Lynn Federle Orr. The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2011.

- Riggs, Terry ‘The Awakening Conscience,’ William Holman Hunt, Tate Gallery, (March 1998)

- Hunt, William Holman., Richmond, William Blake. Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Collected Works of W. Holman Hunt with a Prefatory Note by Sir Wm. B. Richmond: Ernest Brown & Phillips, The Leicester Galleries, London, October-November 1906. United Kingdom: Ernest Brown & Phillips, 1906.