What is Trompe l’oeil?

Trompe l’oeil (sometimes stylised as trompe-l’œil or trompe loeil) is a French term that, when literally translated, means ‘to deceive the eye’. It is an art technique that uses optical illusions for mimetic effect or to push the boundaries of nature, creating puzzling realities.

Trompe l’oeil is often used to describe paintings that use this type of optical illusion technique. The term primarily denotes two modes in flat art: the use of perspective in both wall and easel painting, as well as quadratura, a type of illusionistic ceiling painting. In both instances, the viewer’s eye is manipulated through linear or forced perspective.

Trompe l’oeil techniques continue to be used by contemporary artists to create reality-bending works. The method is by no means limited to painting, however, as Trompe l’oeil murals are also extremely popular. In addition, it can be used to refer to anything that tricks the eye, be it in film or fashion.

History of Trompe l’oeil

The ability to imitate nature totally has captured the collective imagination of artists for millennia. In his work, the Natural History, Pliny the Elder recounts the painting competition between Zeuxis and Parhassius held to determine the better artist. In the tale, Zeuxis unveils his work: grapes so lifelike that birds fly down to try and eat them. When trying to unveil the painting by Parhassius, it is revealed that the curtains thought to hide the work was in fact painted themselves. The story ends with Zeuxis admitting defeat, saying it is one thing to fool an animal but another to fool man.

This story was repeated time and time again in treatises on painting. From the Renaissance on, artists tried to emulate their classical predecessors to ultimately replicate nature. The advent of techniques such as linear perspective and foreshortening used to achieve naturalism are closely linked to the development of trompe l’oeil and are often used together for added effect.

Trompe l’oeil Painting

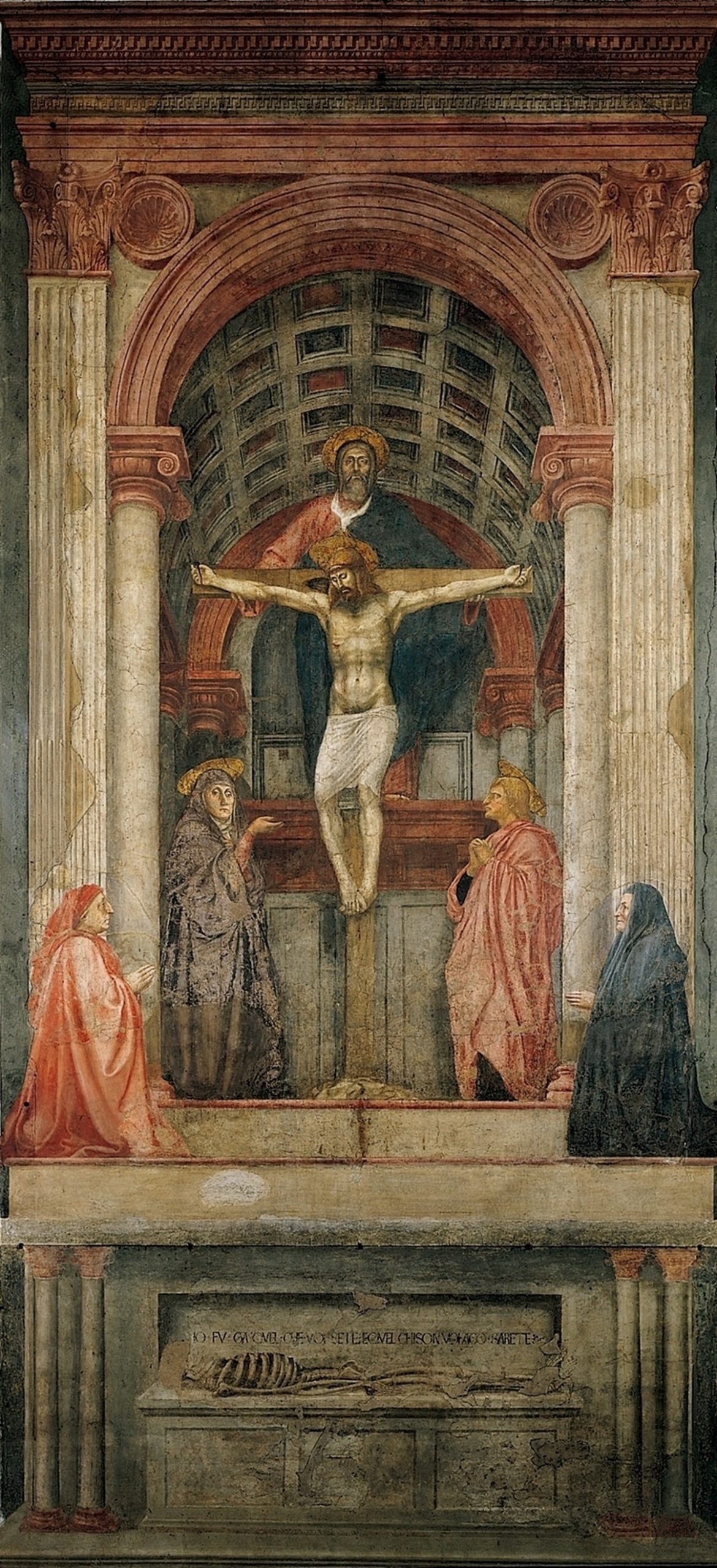

Though trompe l’oeil can be used to enhance the impression of reality, artists such as Leonardo envisioned painting as an open window to another world altogether. This idea is encapsulated by Masaccio’s The Holy Trinity, painted like an altar in which Christ, the Virgin and St John the Baptist miraculously appear. In incorporating the surroundings of Santa Maria Novella, and using fictive, trompe l’oeil elements such as pillars and a coffered barrel vault ceiling, Masaccio was able to enhance this illusionistic depth.

Trompe l’oeil as a technique is grounded in linearity, artists using strong horizontal and rectilinear forms to achieve a certain effect. This is particularly evident in ceiling painting. Quadratura incorporates foreshortening among other tools to create the illusion of three-dimensional space.

The technique di sotto in sù –or seen from below – is an early development of this. Exemplified in Mantegna’s ceiling painting in the Ducal Palace in Mantua, which depicts an oculus – or a circular opening in a dome – revealing a blue sky. This opening is surrounded by an ornamental balustrade around which putti and other figures look down onto the viewer. Later examples of quadratura, such as the work of Andrea Pozzo, continued this use of imagined architectural elements to extend and elevate pre-existing structures.

Trompe l’oeil outside of Italy

Although trompe l’oeil was a common technique used during the Italian Renaissance – as well as the Baroque period – it was by no means limited to Italy. From the 15th century onwards, the technique was used by painters across Europe and the US.

Works by the Dutch master, Evert Collier, showcase how the use of parallel lines in the guise of everyday objects, such as a letter rack, add to an illusion of three-dimensionality.

The Early Netherlandish artist Petrus Christus used small trompe l’oeil elements such as flies – as can be seen in Portrait of a Carthusian – in his portraits to further blur this line between the real and the painted. Likewise, techniques like grisaille – or the use of grey-scale – and faux marbling and wood graining help create the illusion of reality.

Later Uses of Trompe l’oeil

Trompe l’oeil continued to be a popular motif across fine and decorative art. In his famed work Escaping Criticism, 19th century Spanish Painter Pere Borrell del Caso incorporates a painted frame to make the figure appear as if they are coming forth from their plane into the realm of the viewer.

The 19th-century American painter William Harnett became renowned for his trompe l’oeil still life paintings. Using similar techniques to the aforementioned Collier, such as carefully placed lines and shadow, Harnett is able to make an ordinary scene, like a pile of books, appear real.

Trompe l’oeil has also been used in furniture and interior design. This was by no means a new development. The famed studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, which dates to the late 15th century, used intricate intarsia work to give the illusion of three-dimensional interiors, including opened cabinets, books, and instruments. Cabinets, tables and other furniture had trompe l’oeil elements, such as a deck of cards, to both fool and amuse viewers.

Trompe l’oeil: Modern art and Beyond

In contemporary art, the definition is less fixed. The term trompe l’oeil can be used to describe works in other media, such as ceramic or hyperrealist sculpture, that achieve the true to life appearance of another object or being.

Trompe l’oeil has found use in public works to enhance buildings and to create puzzling realities. A famous example of this is the monumental trompe l’oeil mural for the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami, created by American muralist Richard Haas, which has sadly now been destroyed. The building facade was painted to appear like an arch that opened up, with another building in the fore. This was not a work of fiction, as the building in the mural is one that was hidden by the wall.

Trompe l’oeil murals equally play with fantasy and realistic imagery. The contemporary artist Jenny McCracken creates illusionistic paintings on walls and floors, that appear to spring to life in front of the viewer when viewed from a certain direction.

Recently, trompe l’oeil and the power of optical illusion has been used in the media, including in guerilla marketing campaigns. In 2011, Copenhagen Zoo launched a campaign that included a large snake wrapped around city buses.

Considering the impact trompe l’oeil has had, it is no wonder that artists continue to use pictorial and spatial illusionism to bend the world around us, blurring the boundaries between the realistic and fictional.

Notable Trompe-lœil Artworks

William Harnett, The Banker’s Table, 1877, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, the Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, c. 1478-82, wood intarsia, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Richard Haas, Old Mural from the Fontainebleau Hotel, 1986-2003, Miami.

Jenny McCracken, A Flight of Fancy, Mareeba, Australia.

Sylvia Hyman, Crate of Books and Things, 2002, ceramic stoneware.