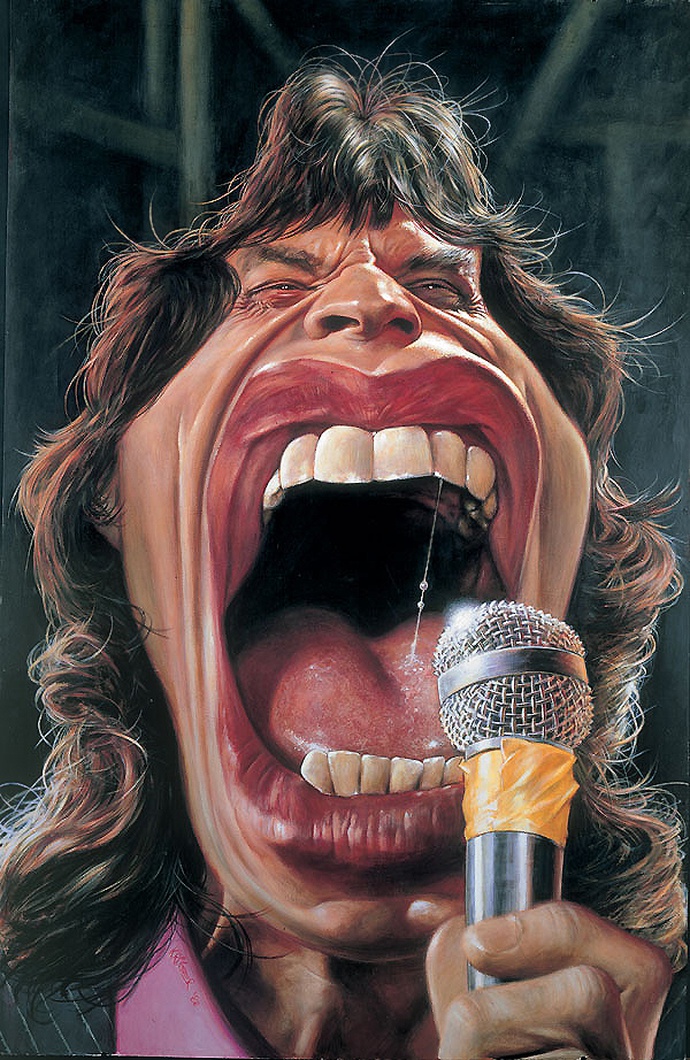

The caricature is a technique based on methods of redefining portrait representativeness by overemphasizing certain characteristics of physical appearance. With the aim of visually evoking the unique characteristics of certain individuals, groups or situations, the caricature developed a visual language understandable to the widest audience. Depending on the covered topics, the caricature can be comic, grotesque, portrait, or satirical. The most important representatives of this technique are William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, Isaac Cruikshank, Honoré Daumier, Gaspard-Felix Tournachon Nadar, Marjorie Organ Henri, Luigi Borgomainerio, Nikolai Stepanov, Melchiorre Delfico, Emile Cohl, David Levine.

Notable Caricatures

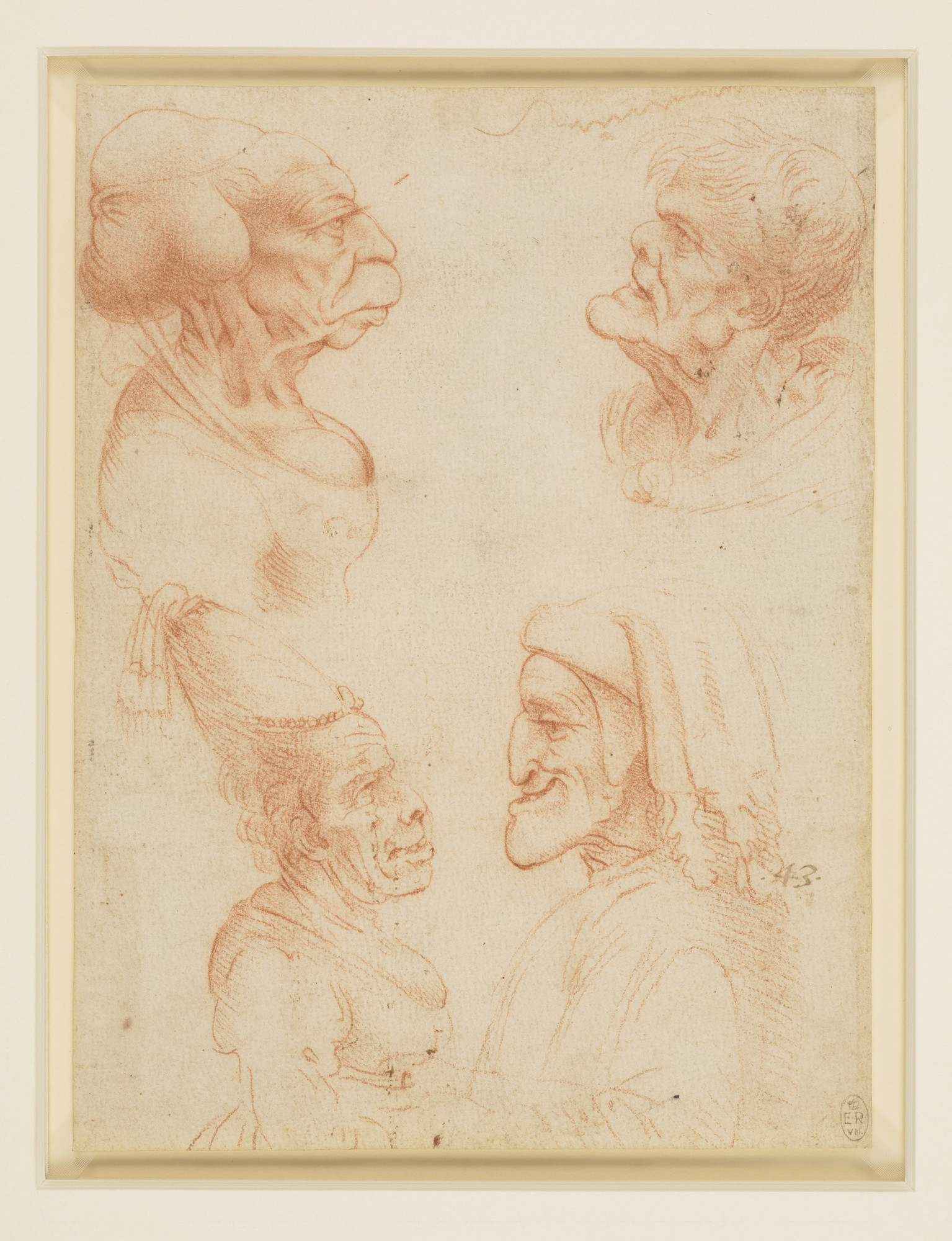

Renaissance Origins of Caricature

The term caricature comes from the Italian word caricare which means to load or to exaggerate. The first traces of what we consider caricature today can be found in the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. There are many original drawings and even more copies of these drawings in which Leonardo experiments with the representation of human physiognomy. It is unclear whether humor was the starting point of these works by Leonardo, but it is more certain that these are studies of the form of facial deviations. The drawings of the brothers Annibale and Agostino Carracci had a certain comic component. During the last decade of the 16th century, they played with the canonical representation of the human figure and its harmonious qualities by clearly positioning humor as the initial idea for the works.

Caricature in the 17th century

Italian art of the 17th century brought an increasing degree of independence to caricature as a separate genre. The famous painter and sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini made numerous drawings guided by the principles of humorous representation. Pier Leone Ghezzi was a very successful caricaturist and pioneer of satirical caricature. Thanks to the London publisher Arthur Pond, the caricatures of Pier Leone Ghezzi, Annibale Carracci, and Carlo Maratti became famous throughout Europe.

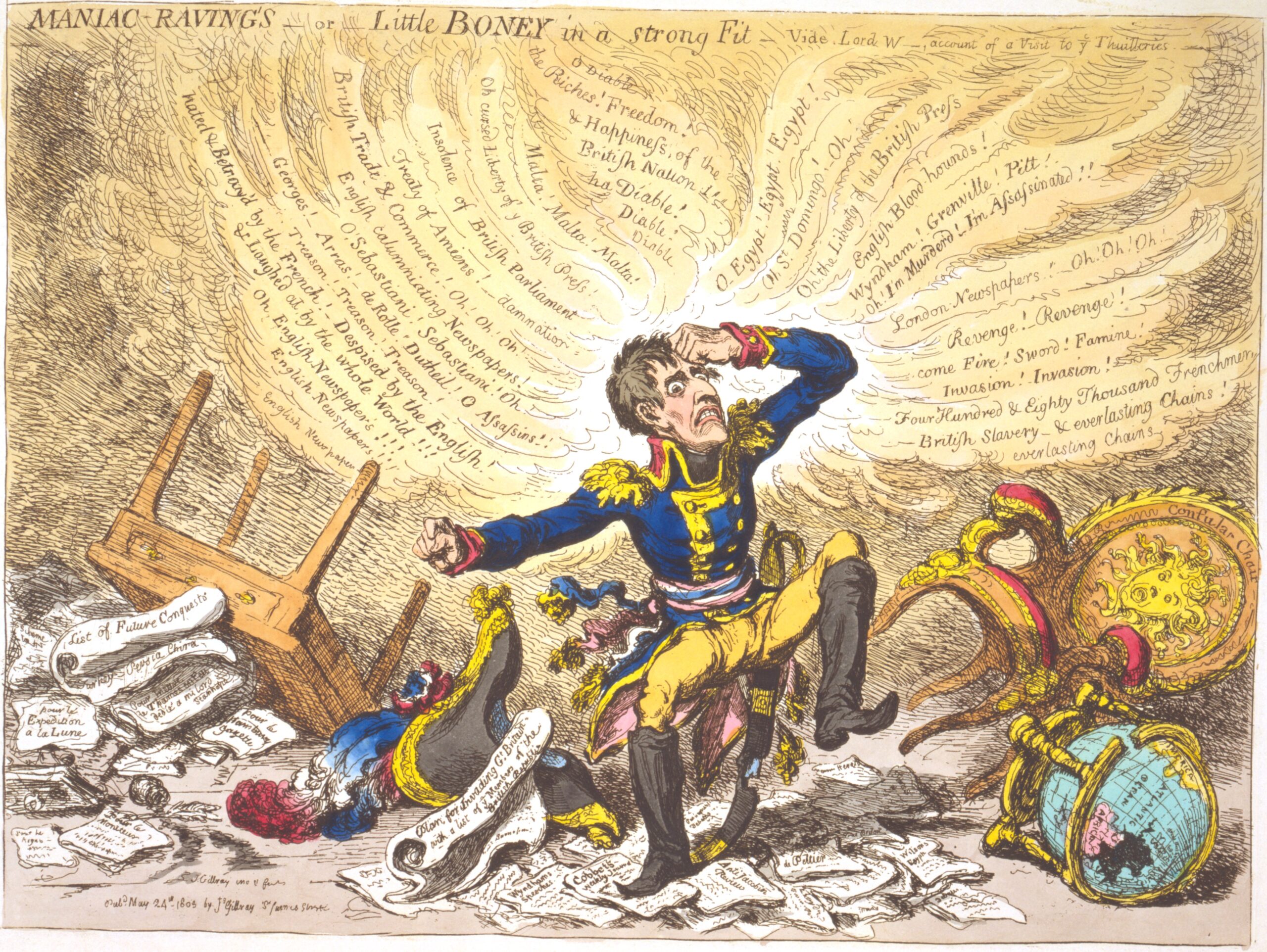

Caricature in the 18th century

During the 18th century, caricature flourished in European culture, becoming an increasingly popular genre in Italy and France, as well as in Germany and England. This was greatly contributed to by the growing influence that the press received in public. Whether published in separate publications or as part of a newspaper, the caricatures corresponded and conveyed messages to a large number of people. The audience that the caricature gained grew much faster than the audience that based its information on the written word precisely because of the high rate of illiteracy. Therefore, moralizing compositions aimed at teaching the broad masses and generating desirable moral norms in society were a great success. William Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress or Marriage a la Mode are perhaps the most famous representatives of this wave, which shaped the visual language of caricature into morally didactic frameworks.

Caricature in the 19th century

The industrial revolution and innovations in the field of printing have led to increasing newspaper circulations. The development of the railway enabled these circulations to be distributed throughout the country at an unprecedented speed. As part of the wider phenomenon of the expansion of the print media, the caricature has thus become a powerful means of influencing public opinion. The radical changes that the French bourgeois revolution caused in European culture initiated the creation of a new political culture in which the press played an important role as a field of political reckoning. In these conditions, an engaged, critical modern caricature developed. Thomas Nast is a pioneer of political caricature in the United States. George Cruikshank used a satirical form of caricature to represent various elements of social deviations in Britain. Yet Honore Daumier is recognized as the father of modern caricature. This artist created a magnificent opus of caricatures that were published in numerous French magazines, the most important of which was La Caricature. Due to criticism in the press directed at King Louis Philippe, Honore Daumier ended up in prison. The growing influence of this art form led to its ban in the mid-1830s.

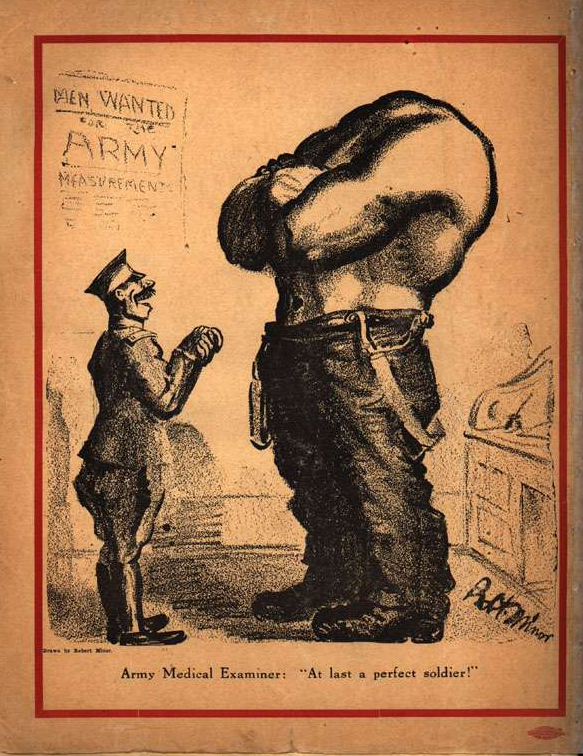

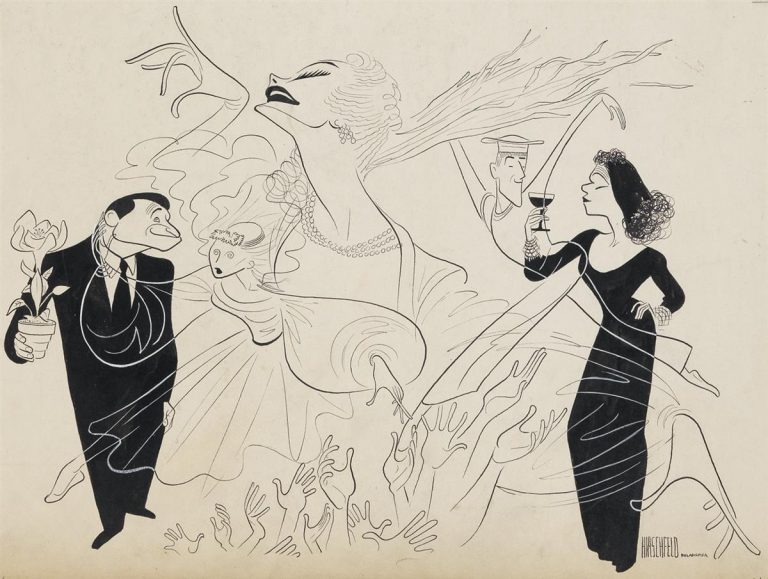

Caricature in the 20th century

Caricature experienced a significant expansion during the first and especially during the second half of the twentieth century. The growing influence of the print media, which lasted continuously until the advent of television, also meant the growing influence of printed caricatures in public. Satirical political caricature came to the fore, especially during the First and Second World Wars. A sharp, critical attitude towards political circumstances was maintained by caricaturists in the West, while in the Eastern Bloc this medium was used almost exclusively for propaganda purposes. As an example of the symbiosis of caricature form and the new most influential medium of television, a satirical series or puppet show Spitting Image was created. It was broadcasted from 1984 to 1996 in Great Britain. This series has influenced the emergence of many related formats around the world.

Development of caricature techniques

During its centuries-long development, caricature was created in various techniques. As Renaissance caricatures were often created in the form of studies of human physiognomy without the intention of publishing, these caricatures were made as charcoal drawings or as pen and ink drawings. Over time, caricatures in the etching technique became more and more common as a result of the printing of numerous newspapers that contained caricatures. Although many artists still insist on hand-drawing the entire work, caricatures are increasingly being created in various drawing software, due to the fact that the internet is taking precedence over traditional print media.

Notable Artists

- Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674 – 1755)

- William Hogarth (1697 – 1764)

- Thomas Rowlandson (1757 – 1827)

- George Bickham the Younger (c. 1706–1771)

- Richard Newton (1777 – 1798)

- Isaac Cruikshank (1764–1811)

- George Murgatroyd Woodward (1765–1809)

- Henry Bunbury (1750 – 1811)

- James Gillray (1756–1815)

- James Sayers (1748 – 1823)

- John Kay (1742 – 1826)

- William Heath (1794 – April 7, 1840)

- John Doyle (1797 – 1868)

- George Cruikshank (1792 – 1878)

- Honoré Daumier (1808 – 1879)

- Gaspard-Felix Tournachon Nadar (1820 – 1910)

- Marjorie Organ Henri (1886 – 1930)

- Luigi Borgomainerio (1836 – 1876)

- Nikolai Stepanov (1807– 1877)

- Melchiorre Delfico (1825 – 1895)

- Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846 – 1905)

- Emile Cohl (1857 – 1938)

- Sam Berman (1907 – 1995)

- David Levine (1926 – 2009)

- David Low (1891 – 1963)

- Marc Sleen (1922 – 2016)

- Predrag Koraksić Corax (1933)

- Ranan Lurie (1932)

- Gerald Scarfe (1936)

- Oğuz Aral (1936 – 2004)

- György Rózsahegyi (1940-2010)

- Dušan Petričić (1946)

- Massoud Mehrabi (1954 – 2020)

Related Art terms